(Part I.)

The last two nominated films of 1947 dealt with the same topic; one was a cloyingly overt (and successful) Oscar-grab by the embittered and entitled producer of 1944’s Wilson (see below), while the other was a compromise solution to the ever-present and ever-annoying problem of the Hays Production Code. This latter film was Crossfire, an early Robert Mitchum vehicle that tells of an investigation into a seemingly motiveless murder of a seemingly random New Yorker by one of a group of returning GIs.

In the end it turns out there is a motive, of course…this isn’t a David Lynch movie. But before that revelation it’s a tough, twisting whodunit: the suspects are a completely innocent, simply naïf trying to get back to his sweetheart, and an obviously-lying, hate-filled bigot who obviously tells hateful, bigoted lies throughout the entire film. I won’t ruin it for you by revealing which is the killer, but I will spoil the motive: pure and simple anti-Semitism. The film makes it clear that being Irish is no cakewalk, either.

“Once, at the Four Seasons, my father was seated at a table that didn’t offer an unobstructed view of the saxophonist. So don’t tell me about hardship.”

“Once, at the Four Seasons, my father was seated at a table that didn’t offer an unobstructed view of the saxophonist. So don’t tell me about hardship.”

The film rather smartly limits itself to just one unrealistic monologue about the evils of intolerance, focusing instead on crafting a solid film noir, but given its lofty intentions ends up falling a bit short. I think it would have been better, if perhaps not nominated for Best Picture, if it hadn’t attempted to turn a simple murder into a soapbox for the problems of society. When it isn’t preaching, it’s a fine film, and the lead Robert employs a very clever trick to catch the murderer…a simple yet tense and effective climax that exemplifies the best qualities of the genre.

It’s worth mentioning that in the source material, a novel called The Brick Foxhole, the murder victim is homosexual rather than Jewish. Naturally, the Hays Code prohibited the filmmakers from addressing the subject of homosexuals, even in the context of suggesting that they shouldn’t be murdered when they don’t offer guests a drink, so they had to make adjustments to ensure the fragile morality of the American public wasn’t corrupted. And, of course, to give the 1947 Oscars a theme.

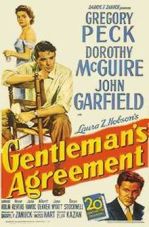

The winner by design was Gentleman’s Agreement, a film I’d been looking forward to revisiting since I started this project. I remembered it being a phenomenal film, one of the highlights of the decade, and reviewing it in the context of everything that came before it, and as part of the huge upswing in quality exhibited by Hollywood in the postwar years, seemed like the perfect way to cap off the Academy’s first 20 years. Hell, in Part I, I even describe it as “one of the best films of the 1940s”.

And all I could think when it was over was, “What the fuck was that?”

The first 80 minutes or so are great, if a little on-the-nose (literally everyone in New York City who is not Gregory Peck or his mother is a closet anti-Semite), but then the film goes seriously off the rails. The last 40 minutes are an interminably dull procession of preachy monologues that contribute nothing to the narrative or to the ideas expressed in the rest of the film; what should be a concise wrapping up instead feels like Darryl F. Zanuck smashing you repeatedly in the face with a brick with the words “Anti-Semitism is bad” scrawled on it. When it ends with Peck running to the arms of his bigoted, WASPy fiancée, all one feels is relief that it is over and we don’t have to witness the inevitable disintegration of their marriage and their capacity to love (though arguably that would make a better movie).

Peck’s love interest Kathy Lacey, played by Dorothy McGuire, is really one of the most abhorrent humans in the history of film. I understand that the point of her character is to illustrate that those who profess to be tolerant are actually the worst bigots of all, just waiting for something to bring it to the surface, but this is played up to such a ridiculous degree that just about everything she says after roughly the 20-minute mark is dripping with entitlement and ignorance. The film works hard to present her as simply unaware of the harm she causes through indifferent racism, but the truth is she is fully aware of herself and chooses to remain this cancerous drain on the collective value of the human species. This is the person we’re supposed to hope winds up with Gregory Peck, and it’s worth pointing out that she actively loathes him for his social conscience.

“I just can’t talk to you about being a spoiled narcissist and a horrible bigot…you just twist it and make it sound awful!”

“I just can’t talk to you about being a spoiled narcissist and a horrible bigot…you just twist it and make it sound awful!”

—Disturbingly close to an exact quote

In the end, John Garfield turns her around (as he did so many women), Our Hero rushes back to her as the music swells, and we’re supposed to feel good that in the end, one rich brat caved in to feelings of white guilt for long enough to help out an unfortunate a less fortunate person. Yay, conveniently timed and insincere tolerance. The movie hopes we don’t think too much about the fact that she will absolutely cave and turn on him the second she feels threatened by her social circle, because she is an unapologetically bad person.

Of course, this isn’t inconsistent with the film’s lazy treatment of its subject matter. From beginning to end, caricatures are favored over characters, and the narrative exists only to serve the preordained message. It’s the approach to social issues that Crash would adopt sixty years later, with even less success.

It should come as no surprise that the man behind it all, Darryl F. Zanuck, also produced 1944’s Wilson, another ridiculously preachy attempt to be cutting and socially relevant. He made Gentleman’s Agreement with the singular intention of winning Best Picture to make up for the fact that the Academy justly denied him the Oscar for that travesty (since winning over Citizen Kane in 1941 didn’t satisfy him). So, seeing that “message” films like The Lost Weekend and The Best Years of Our Lives were hot, he chose the most incendiary topic he could think of, made the film, and basically dared the Academy not to honor him.

“I knew this film would succeed in…uh, raising social awareness and stuff.”

“I knew this film would succeed in…uh, raising social awareness and stuff.”

All in all, re-watching this film was an enlightening experience, just not in the way I expected. And so we come to the end of twenty years of Oscars, on the verge of the slow shift to Technicolor that was the 1950s. I feel confident that a healthy dose of John Huston and Laurence Olivier in 1948 will remove the rather stale and uncomfortable taste left by Gentleman’s Agreement. Onward!

Pingback: 27th Academy Awards (1954) – Part II | Oscars and I

Pingback: 28th Academy Awards (1955) – Part I | Oscars and I

Pingback: 31st Academy Awards (1958) – Part II | Oscars and I

I really didn’t like the Gregory Peck character for the simple reason that he subjected his son to all that for a magazine article. I can certainly understand him doing it all to himself, but a parent using the kid as a part of a social experiment… Count me out.

LikeLike

I read this comment right after your one about Shane, and thought we were still in 1953, and thought my memory was going…I kept thinking, “Did he even HAVE a son in Roman Holiday?!”

Very good point! His son goes through a lot.

LikeLike